Mini review Article / Open Access

DOI:10.31488/bjg.1000124

Incarcerated Meckel Diverticulitis with Two Enteroliths. An Unusual Disease in the Adulthood

Decanini Terán Cesar1, Parada Pérez Fernanda2, Garibaldi Bernot Mauro3, Noriega Usi Víctor Manuel*4

1. Chief of surgery, American British Cowdray Medical Center, Mexico City, Mexico

2. Surgical resident, American British Cowdray Medical Center, Mexico City, Mexico

3. Surgical resident, American British Cowdray Medical Center, Mexico City, Mexico

4. Associate. Profesor, American British Cowdray Medical Center, Mexico City, Mexico

* Corresponding author: Víctor Manuel Noriega, Department of general and digestive surgery. American British Cowdray Medical Center, Mexico City, Mexico. Usi. Sur 136 No. 116, Consultorio 1A, Las Americas, 11850, CDMX, México.

Abstract

Meckel diverticulum (MD) is the most common malformation in the gastrointestinal tract (GI). MD length is between 2 and 3cm. When the size is above 5cm, it is called Giant Meckel. Although the majority of large MD are asymptomatic, complications may develop, which include small bowel obstruction. Obstruction due to an enterolith is a rare finding. Case presentation: The patient is a 41-year-old male with severe abdominal pain and constipation diagnosed with intestinal obstruction due to Meckel diverticulitis. The tip was adherent to the umbilicus and perforated. The MD passed through an hernial defect in the greater omentum. Between the incarceration and diverticular tip, two fecaliths caused the obstruction. We do a diverticulectomy with no incidents. Discussion: MD is a true diverticulum on the ileum. 50% have ectopic mucosa. The majority of patients are asymptomatic, with an estimated lifetime risk for symptomatic disease of 4.2%. Complicated MD presents with diverticulitis, intestinal obstruction, and bleeding. Treatment includes diverticulectomy and segmental intestinal resection. Conclusion: Meckel diverticulitis in adults is unusual. The surgeon must remember at all times the disease, pathophysiology, and surgical treatment.

Keywords: Meckel diverticulum, MD, Meckel diverticulitis, Small bowel obstruction, fecalith, enterolith

Introduction

Meckel Diverticulum (MD) is the most common congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract. It results from incomplete obliteration of the vitelline duct in about 2% of the population. Cells lining the MD are pluripotent and can be differentiate into gastric, pancreatic, or colonic. MD measures between 2 and 3 cm in length [1-6]. When the size is 5 cm in length or more, it calls Giant Meckel Diverticulum [8]. Patients with a giant MD usually remain asymptomatic. However, they have a 4 to 6% lifetime risk of developing complications [9]. Mechanical small bowel obstruction in a complicated MD includes intussusception, adhesions, volvulus, and neoplasm. Obstruction due to an enterolith is a rare finding.

Computed tomography may help in the preoperative diagnosis [10]. We present a case of small bowel obstruction secondary to Meckel diverticulitis with two enteroliths. The diverticulum had a perforation at the tip, which was adherent to the umbilicus.

Case Presentation

The patient is a 41-year-old male who came to the emergency room with a five-day history of moderate to severe abdominal pain and constipation. He had abdominal bloating, vomiting and was unable to pass gas. He took polyethyleneglycol five days before and had transient relief of pain and constipation. On the day of his admission, he had a fever of 39ºC, severe abdominal pain, and abdominal bloating.

On physical examination, he was tachycardic with a pulse rate of 101 beats per minute, with severe abdominal pain and distention, slow bowel movements, rebound, and tenderness. The blood test revealed leukocytosis of 18.5 103/uL with left shift and a C-reactive protein of 4.09 mg/dl. Procalcitonin was normal (0.18 ng/ml). Other findings were hyponatremia (126.6 mmol/L), which later was associated with inappropriate antidiuretic hormone ADH release.

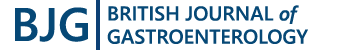

An outpatient CT scan performed hours before his admission reported a radiologic diagnosis of biliary ileus. A foraging radiopaque 2 cm body was located within the ileum's lumen about 30 cm of the ileocecal valve. However, the gallbladder was normal without pneumobilia to sustain the diagnosis. A new CT scan revealed a 2cm foreign body within the intestinal lumen, in association with a 50 x 28 mm tubular outpouching protruding from the ileum, with thin walls and heterogeneous content, fat striation, free fluid, and mechanical obstruction in the distal ileum (Figure 1). The patient underwent an urgent laparotomy due to intestinal occlusion secondary to a foreign body.

Figure 1.entherolith is observed inside the intestinal lumen (a). Fat striation around the diverticulum (b).

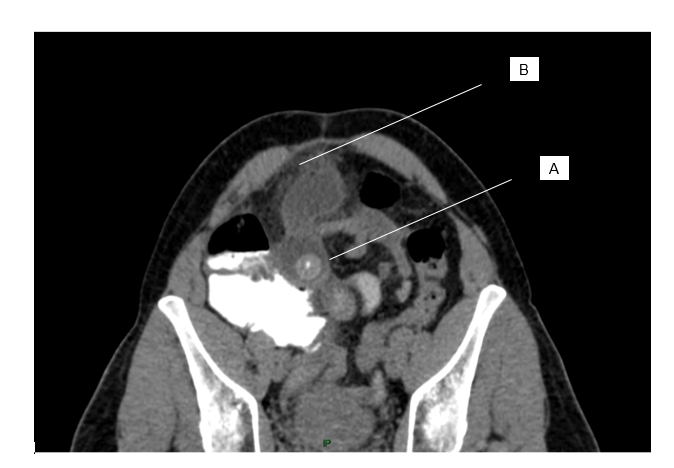

While opening the abdominal cavity, we encountered a perforated Meckel's diverticulum. The perforation was at the tip of the diverticulum, which was adherent to the umbilicus. There was purulent and fecaloid fluid. The diverticulum emerged from the ileum's antimesenteric border, 90 cm from the ileocecal valve, then passed through a hernial defect in the greater omentum in which it was incarcerated (Figure 2). Distally, between the incarceration and diverticular tip, we found two fecaliths of 2 and 3cm (Figure 3). These fecaliths were the ones observed as one radiopaque foreign body at the CT scan. We divided the greater omentum to release the incarcerated segment, do a diverticulectomy with a 60mm linear stapler, and subsequent manual reinforcement of the staple line. The pathology report confirmed Meckel's diverticulitis, with no evidence of ectopic tissue or neoplasia. The patient's condition improved, and he was discharged on day six.

Figure 2.The diverticulum incarcerated in the greater omentum. Figure 2B shows the fecaliths inside the diverticulum (a), the site of incarceration (b), and the diverticular base (c)

Figure 3.Two fecaliths of 2 and 3cm located between the strangulated segment and the diverticular tip.

Discussion

Meckel's diverticulum (MD) is a true diverticulum on the ileum developed during embryogenesis. It results from incomplete obliteration of the omphalomesenteric or vitelline duct. It is the most prevalent congenital gastrointestinal anomaly, accounting for 97% of vitelline duct pathologies. The first description is by Hildanus in 1598 and received his name after Johann Friedrich Meckel established its embryologic origin in 1809 [1-6].

Prevalence is between 0.3% and 2.9%. Its location is in the antimesenteric border in the terminal ileum. It is located between 7 to 200 cm from the ileocecal valve (mean of 52 cm), a length of 0.4 to 11 cm (mean of 3 cm), and a diameter of 0.3 to 7 cm (mean of 1.58 cm) [1-3,5].

In 50% of cases, MD have ectopic mucosa. The most common ectopic tissues are gastric and pancreatic mucosa, and they represent 97% of the cases. Duodenal and colonic tissue is a rare finding. Ectopic tissue is associated with symptomatic MD, particularly with gastrointestinal bleeding [2].

The majority of MD are asymptomatic, with an estimated lifetime risk for symptomatic disease of 4.2%. When symptomatic, more than half of the patients are younger than ten years, and the prevalence of symptomatic disease decreases with age. Incidence is similar in men and women, but the symptomatic disease is developed more often in men [5].

The diagnosis is made by ruling out other pathologies. Symptoms like abdominal pain, vomiting, fever, and bloody stools often overlay with other abdominal emergencies. Complicated MD usually presents with diverticulitis, intestinal obstruction, or bleeding. In adulthood, the most frequent complication is an intestinal obstruction (35.6%), followed by diverticulitis (29.4%) and bleeding (27.3%). In the pediatric population, obstruction is the most common complication (47%), followed by bleeding (25.3%) and diverticulitis (19.5%).

Parvanescu et al. reported in a retrospective review that diverticulitis (35.1%) and obstruction (35.1%) are equally in proportion. They found that diverticulitis occurs more often in patients over 40 years old, while GI bleeding is more common in patients under 40 [3].

Specialized ectopic mucosa may be present inside the diverticulum. GI bleeding is usually the result of acid secretion and ulceration by gastric mucosa inside the intestinal lumen. This entity is the leading cause of painless GI bleeding in children under two years.

Meckel diverticulitis is easily confused with acute appendicitis, and like this one, it may gangrene and perforate (0.5% to 7.3%). Other complications are abscess or fistula formation. The causes of mechanical obstruction are volvulus, intussusception, enterolith formation, or incarceration within an hernial defect (Littre's hernia) or an internal abdominal hernia [11]. Enteroliths (faecoliths, bezoars, or gallstones) in MD are uncommon. They result from precipitation and deposition of enteric contents associated with hypomotility and stasis [9,10].

MD is challenging to diagnose clinically and radiologically. Reports estimate a 6% average mortality for this pathology. The elderly are more affected because of delayed diagnosis and treatment. Only 5.7% of patients will be diagnosed preoperatively by imaging due to the studies' low sensitivity and specificity. To find an MD, one needs to suspect the disease and actively search for it.

There are two studies to diagnose gastrointestinal bleeding. Arteriography of the superior mesenteric artery demonstrates the vitelline artery as a pathognomonic finding, and Scintigraphy with Tc-99m pertechnetate demonstrates focal uptake in the MD. For a definitive diagnosis, direct visualization is possible with double-balloon enteroscopy, capsule endoscopy, or surgery [11]. CT scan may be useful when there is extravasation of contrast in the terminal ileum loops.

Abdominal CT scan is useful in diverticulitis, demonstrating inflammatory mesenteric changes, localized fluid, or air-fluid collections. In high resolution tomography, the diverticulum it is seen as an outpouching in the terminal ileum. In obstruction, CT scan demonstrates the transition point behind the affected zone [12].

All symptomatic MD will need surgical resection. The treatment options are diverticulectomy or segmental resection of the small bowel. The type of procedure depends on two factors: ectopic tissue's presence and its location, and the diverticulum base's integrity. It is not possible to see ectopic tissue macroscopically or by palpation. The height-to-diameter rate is useful to classify diverticulum in long (ratio of >2) or short (<2). When the diverticulum is longer, the possibilities are that the ectopic mucosa is in the distal end. A diverticulectomy is a good option in these cases. Short MD may have ectopic mucosa at the base. For these cases, ischemic MD or perforation near the base, the treatment is intestinal resection with primary anastomosis. In patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal resection is the preferred method to assure full resection of ectopic tissue [1-6].

A new intervention may be necessary to complete segmental resection when the pathologist finds residual ectopic tissue after a diverticulectomy. There are no differences between the laparoscopic and open approaches. The morbidity is 5.3%, with ileus and wound infections being the most commonly reported complications (3-6).

The treatment of an incidental MD during laparotomy is controversial. The surgeon will have to individualize every decision according to risk factors that may predict future symptoms. There are four criteria postulated by Mackey and Dineen to predict future complications: Patient younger than 50 years, male gender, diverticulum length >2 cm, and the presence of ectopic mucosa. If one of these criteria is present, the probability of developing symptoms is 17%, two is 25%, three is 42%, and four criteria is up to 70%. Only one positive criterion is sufficient to recommend surgical management [5-6].

Another condition to keep in mind is the risk of developing neoplasia. The prevalence of tumors in symptomatic MD varies from 0.5% to 5.1%. Most of them are benign. Also, MD has a 70-fold higher risk of developing cancer than any other site in the ileum. Neuroendocrine tumors (NET) are the most frequent malignancies (63%), followed by GIST (10%), adenocarcinoma (5%), and pancreatic epithelial neoplasia (5%). Neoplasia occurs more often in males (74%), with an average age of 58 years. In NET cases, 26% to 33% will have metastases at diagnosis (in lymph nodes and liver). Van Malderen et al. recommend prophylactic removal of asymptomatic MD to avoid the risk of leaving cancer [5-7].

Conclusion

There are few reports with pictures of perforated MD with enteroliths reported in the literature. Symptomatic Meckel diverticulitis in adults is unusual. Diagnosis usually is achieved while discarding other pathologies. Although it is a rare disease, the surgeon should keep in mind the basic concepts and surgical treatments available. When asymptomatic, surgical resection is the preferred treatment to avoid future complications.

References

1. Malik AA, Bari S, Wani KA, et al. Meckel's Diverticulum – Revisited. The Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(1):3-7.

2. Hansen C, Soreide K. Systematic review of epidemiology, presentation, and management of Meckel's diverticulum in the 21st century. Medicine. 2018;97(35):1-9.

3. Parvanescu A, Bruzzi M, Voron T, et al. Complicated Meckel's diverticulum. Presentation modes in adults. Medicine. 2018;97(38):1-6.

4. Wong CS, Dupley L, Varia HN, et al. Meckel's diverticulitis: a rare entity of Meckel's diverticulum. J Surg Case Rep.2017;1:1-3.

5. Lindeman R, Soreide K. The Many Faces of Meckel's Diverticulum: Update on Management in Incidental and Symptomatic Patients. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22:1-8.

6. Blouhos K, Boulas KA, Cialis K, et al. Meckel's Diverticulum in Adults: Surgical Concerns. Front Surg. 2018;5(55):1-4.

7. Van Malderen K, Vijayvargiya P, Camilleri M, et al. Malignancy and Meckel's diverticulum: A systematic literature review and 14-year experience at a tertiary referral center. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;6(5):739-747.

8. Grinsell D, Donaldson E. Giant Meckel's diverticulum with enterolith formation. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:968-969.

9. Nunes QM, Hotouras A, Tiwari S, et al. Gangrene due to axial torsion of a giant Meckel's diverticulum containing multiple stones in the lumen: a case report. Cases J. 2009;18(2):7141.

10. Wauters L, Peeters K, Van Hootegem A, et al. Meckel’s enterolith : a rare cause of mechanical small bowel subobstruction. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2018;81(4):534-537.

11. Modi S, Pillai SK, DeClercq S. Perforated Meckel's diverticulum in an adult due to faecolith: A case report and review of literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;15:143-145.

12. Platon A, Gervaz P, Becker C, et al. Computed tomography of complicated Meckel’s diverticulum in adults: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging. 2010;1(2):53-61.

Received: Jan 21, 2021;

Accepted: Jan 28, 2021;

Published: February 03, 2021.

To cite this article : Cesar DT, Fernanda PP, Víctor Manuel NU, et al. Incarcerated Meckel Diverticulitis with Two Enteroliths. An Unusual Disease in the Adulthood. British Journal of Gastroenterology. 2021; 3:1.

©2021 Víctor Manuel NU, et al.